The Trials of Galileo

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Reviews

Fringe Review, Kate Saffin

Equivalent ("Outstanding" Rating)

Equivalent ("Outstanding" Rating)

Low Down

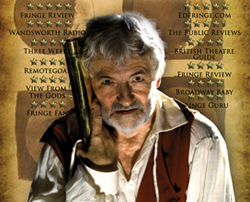

This outstanding one man show is set around the trials of Galileo in 1633 in which he was tried for heresy after demonstrating that the world circled the sun rather than vice versa. Galileo's encounter with the Catholic Church became the defining event for the stormy relationship between science and religion. Nic Young's script and Tom Hardy's performance add up to a powerful chemistry.

Review

In the spring of 1632 Galileo had published a book (after many years work) entitled 'Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'. It was modelled on Plato's dialogues with three speakers - Salviati defends Copernicus's heliocentric astronomy (that the earth circles the sun, not vice versa), Sagredo who is open minded and Simplicio who obstinately defends Aristotelian-Ptolemaic geocentric worldview. This approach allowed him to claim that the book was neutral but the Catholic Church didn't see it that way. In 1633 Galileo was arraigned by the Roman Inquisitor charged with promoting heresy and tried by ten cardinals.

Galileo probably was a genius and a painstaking and careful scientist. However, in his battle with the church he failed to understand that it wasn't a question of proof, but of politics. Something the Vatican cardinals were expert at.

Nic Young's play performed by Tim Hardy is framed by the trials (there were three in all, over several months in the Spring of 1633) and provides and analysis of the key points of dispute and takes us into the mind of the man behind the science.

Galileo was a deeply religious man, he had considered becoming a priest but his father persuaded him to study medicine instead. He qualified as a doctor but eventually become most interested in physics and improved on the early designs of telescopes until he had created one that had could magnify an object to thirty times its original size. Young captures all these biographical points and slips them in almost unnoticed but the real power of the piece is the exploration of how Galileo might have understood and made sense of that which he observed as well as his experience of the trial.

The play begins at the end of the trials when Galileo has, unwillingly, recanted and is about to sign the confession of error. He then weaves in and out of the past as he tells the story of his findings and the trial. One striking aspect of Young's script is the way that he explores Galileo's sense of failure at having signed the confession, at not being willing to die for what he had found, as the early Christian martyrs had. He then goes on to tease out the process of arriving at the proof that the earth circles the sun, to show that it was not the simple discovery that it is often presented as, but a challenging and painful one. God and faith were central to Galileo's life so the challenge of believing what he was seeing wasn't only one for the Catholic church, because, as he says, where revelations are concerned 'God chooses, you don't go looking'. The result is a beautiful character study of a thoughtful, clever and pious man. Add Tim Hardy into the mix as portraying Galileo Galilei and you have a unique chemistry in which we could almost believe we were in Galileo's study.

From the moment that Hardy delivers the first line we know we are in the hands of a consummate performer. He is by turns confident, witty, uncertain, puzzled, reflective, angry and in being so creates an entirely believable Galileo. He has only a tiny stage with a desk, a few papers and his telescope but we feel that we are privileged to be allowed into his study as he finds another letter or paper that might provide the evidence to prove the prosecutor wrong. Despite these constraints Hardy creates the courtroom, the garden of the Vatican, his observatory switching effortlessly into other characters - the prosecutor, Pope Urban VIII - and this variety sustains the pace and makes the piece absorbing throughout.

Galileo could never understand why proving that the earth circled the sun rather than vice versa was in any way heretical - after all the whole universe was God's creation so would he not have arranged it all in the best possible order to work? Did it matter what circled what? In this story are resonances with modern science/faith arguments - less so in this country but very significant in American politics. So, whilst in many ways this is an interesting history lesson, a beautiful character study of a genius, in others this is a provocation to think, to remember that single minded blinkered prosecutors are not only a thing of the 17th Century.

edfringe.com, Norman Bissell

The superb Tim Hardy triumphs as Galileo in this top notch production by Icarus Theatre. His acting is outstanding in a spellbinding story of the conflict between scientific truth and political and religious power that remains highly relevant in today's world. A 5 stars must see for Fringe goers, can't recommend it highly enough. As a Fringe accredited promoter, I'd love to be able to bring it to the Atlantic Islands Centre on the Isle of Luing through The Touring Network.

Public Reviews, Jon Wainwright

We're taken straight into the trial of Galileo and the peculiar workings of the Inquisition. He complains of being addressed in the third person, as though he isn't there, and we appreciate the irony of the judge's objectivity and inquisitiveness (he's anything but). Galileo's guilt is assumed - the man just needs to confess. Tim Hardy is compelling as the great scientist, sometimes sat behind a desk, sometimes standing before us, confiding his deepest fears and hopes, confident in his own achievements and yet surprised at the machinations of the church to which he belongs.

We're left in no doubt as to the consequences of holding the wrong beliefs or publishing the wrong kind of book. Galileo's early training as a doctor has given him an exquisite understanding of the effects of metal on flesh. We know the damage accidents can do - imagine if someone is really trying. No wonder just seeing the rack is an effective "verbal laxative". Galileo shares our incredulity that the church should go to so much trouble to destroy a book. Hardy's expressiveness conveys the absurdity of the charges: what can be so terrible about a book?

After all, an article of faith can hardly be contradicted by a few printed words, or by that which sustains science, reason and evidence. That's the whole point of faith. Why is the church worried? Because Galileo's book is a dialogue between two ideas, and however hypothetical the faithful cannot be offered an alternative. Plus there's the small matter of calling the character who speaks for the pope and the faithful Simplicio.

Hardy wears his Renaissance tunic and gown with the ease of a native of Florence, and has complete mastery of an excellent script. There's a telescope in one corner, and papers scattered about, including a sketch of the moon showing its mountains and valleys - the very image of heresy. The Inquisition's rack has long gone, but we're still looking through that telescope, discovering new knowledge. There is no comfort in ignorance.

Fringe Guru

I had high expectations for Icarus Theatre Collective's play, given the impressive credentials of actor Tim Hardy and Emmy Award-winning playwright Nic Young. And I wasn't disappointed. In The Trials Of Galileo, a piece of history that changed the way we look at the Universe is masterfully brought to the stage.

At 70 minutes, this is long for a one-man show, but don't let that put you off - the solitude only adds to the drama. The scene shifts from Galileo's home in Florence to a courthouse in Rome, and the Papal gardens at the Vatican. Meanwhile, the storyline alternates between Galileo's past - when, with Pope Urban's blessing, he decides to hypothesize about the Copernican heliocentric model - to his present, where he is being held prisoner and charged with heresy.

Tim Hardy's performance is exemplary; not just as Galileo, but also as the judge, the Pope, and the lawyer. In the courtroom scene, it feels almost as if there were two actors on stage. Hardy does full justice to his background, which includes work with the BBC and RSC; he holds the floor on his own, with very little accompaniment in the form of light and sound. Props, too, are minimal, though chosen with an eye to aesthetics. A small table with a pitcher of water stands in the corner, along with a large table displaying his workings, book, and drawings - and finally the all-important telescope, which he has crafted himself.

The script is often excellent. Galileo's frustration is brought out with finesse, as he struggles with his science and his deeply religious Catholicism; his na´vetÚ towards politics, and even the deep-seated dogma that the Church is capable of, are all explored as well. The power of the written word is underlined, and the despondency of a man of science in the face of fanaticism is highlighted.

There are some excellent turns of phrase, as when Galileo tells us that looking through the telescope he felt as if 'the entire Universe had funnelled itself through the tiny eyepiece', and some good instances of humour - the unevenness of the moon's surface is compared to 'drawing moles on the face of Madonna herself'. But even so, there were times when I found the material slightly tiresome, like being in a class about the solar system. It is hard to un-know the science we all consider basic now, and with just one man on stage, there's nothing to distract you from anything you find overly familiar.

But on the other hand, that brought me away appreciating the sacrifice and struggles of great scientists of the past - to discover the truth and fight tirelessly for it. This is a show that blends faith, religion, reason, logic, and art to great effect. Whatever your knowledge of Galileo and whatever your interest in science, you will have something to take away from this absorbing production.

Broadway Baby, Richard Beck

Galileo lived in age when the church reigned supreme, faith was more important than fact and dogma denied discovery. The ages of reason and enlightenment were a long way off. Scientists and free thinkers lived in fear of the inquisition and debate was stifled. The Trials of Galileo sublimely reveals not just the desperate deliberations during trials in ecclesiastical courts but the inner trials experienced by a man of conscience.

Galileo knew from his observations that the sun, not the earth, was the centre of the universe. Copernicus had asserted it mathematically and modelled it but Galileo claimed to have observed it. He was therefore at odds with the church whose geocentric view was an article of faith and so by definition had to be true. Galileo wanted to remain true to being both an astute astronomer and a devout catholic, but that was becoming increasingly impossible: one would have to give way. Was Galileo going to be the hero of heliology or be hounded by heresy?

Tim Hardy's Galileo is not only a man of reason but a reasonable man. He is likeable; he wants to follow his passion, get on with his work and be left alone. The duplicitous Pope Urban and his acolytes however will ultimately not remain enthroned and have their authority and the divine order challenged. During the course of the years spanned by The Trials of Galileo we meet a host of characters whom Tim Hardy sharply defines by voice and gesture. We hear him rant and rage, argue and acquiesce, lament and laugh as he goes from place to place meeting more and more immovable people only to return to the haven of his lonely room and beloved telescope.

It is an enormous tribute to Tim Hardy's captivating skill and abilities as an actor that he can keep his audience focussed for seventy minutes and on a subject that is largely detached from our modern lives. That's not to say that this wordy treatise could not be made more vigorous with some judicial editing and more appealing with additional sound and some visual imagery.

Stage Talk Magazine, Deborah Sims

For me, 2015 was the year of the one-man show. During last year I saw some top-rate productions with a sole performer, so it felt very apt that my first play of 2016 was The Trials of Galileo, performed single-handedly by Royal Shakespeare Company veteran Tim Hardy.

Hardy plays Galileo, the seventeenth-century scientist who was prosecuted for mathematically proving Copernicus's theory that the earth was not the centre of the universe, but that it in fact went around the sun. This heliocentric heresy did not go down well with the Vatican, who promptly banned his book and, by threat of torture, forced Galileo sign a confession to say that he was lying, and that he was awfully sorry and wouldn't do anything so silly again.

The centre of the play is Galileo's confession about the one he is forced to sign. Hardy conveys the battle within himself with real thespian conviction. Galileo knows he is telling the truth. The mathematics is there, for anyone to attempt (and fail) to disprove. But he's not willing to die for his truth. He can't be a martyr. He's not Jesus Christ.

The argument against him is that proof denies faith. But Galileo is very much a man of God. He believes that learning the mechanics of the universe is an act of faith in itself. The impossible battle between truth and Truth, and between faith and Church, is fought in Hardy's delivery. He is two men at once - the man who has made an incredible, world-changing discovery, and the man who is up against the System. He knows what he should say, if he were to be a soldier of the cause, but he does not say it, and the fact that he does not fills him with a palpable sense of shame.

The Trials of Galileo is a classic one-man show. A deep exploration in to character with few bells or whistles, this was all about Hardy. And he shines like the sun.

View from the Gods

The Trials of Galileo

The Hope Theatre

10th February 2015

We all know that the Earth revolves around the sun. Fact. And yet, once upon a time, that wasn't a commonly held belief, and to suggest as much, well, it would have made you seem stupid and/or dangerous. In the early part of the 17th Century, astronomer, mathematician, scientist and dedicated Catholic Galileo Galilei was put on trial for heresy. His studies told him that our planet was not the centre of everything, but at that time, this was in contradiction to how the bible was generally interpreted. Cue a lot of anger and from some very influential people.

In The Trials of Galileo, playwright Nic Young plucks Galileo (Tim Hardy) out of the history books and presents him as a person we can all understand. Oh, he's a genius, but he's fallible, he's frail - he may come up with brilliant treatises, but he can say the wrong thing, and he's an OAP with arthritis and piles. Essentially, he's just as human and mortal as the rest of us, if not more so. Young knocks him off his pedestal and makes him relatable. Galileo is well-spoken and articulate, so when he suddenly breaks out into more colourful language, the unexpected juxtaposition creates humour. He may be a Florentine, but there's a fair bit of British throwaway snark in his dialogue.

The auditorium feels more intimate than usual - the audience curve round the scientist's writing desk, almost echoing the curved shaded moon or sun from his sketches. Hardy moves around the stage, his character agitated by his apparent inability to convince everyone that he has indeed managed to reconcile his faith in God and his belief in science, frequently locking eyes with individual spectators. As he gazes as us from mere inches away, passionately explaining his point of view, the rest of the audience fall away. Dan Saggars' lighting too make the space feel smaller - the edges are shrouded in darkness and the bright yellow lights bear down upon Hardy, again, this evoking the sun. Hardy is clearly an old-school classically trained actor and it's lovely to see this kind of quality in a small theatre pub in central London - you almost feel like you've been let in on a secret.

Ink sketches created by Lou Yates litter the floor - drawings of the planets and the stars scribbled by an excited Galileo trying to prove our planet's rotation. He can't switch off, he's always thinking, always theorising, and the piles of paper reinforce his brilliant energy. Another nice touch is the well finished period costume by Deborah AH Lawrence. In his trial, Galileo is condemned by the devil in the detail, but the production itself leaves no scope for any minor points to derail it. A few minor technical problems aside, there's a lot of polish here.

It admittedly takes a little while to get into the story - no more than ten minutes - then for the remaining hour or so, that's it, you're hooked. The narrative, a one-man dialogue, is broken up with short blackouts indicating the passage of time, with Hardy taking on the voices of the other key characters - the Pope, the judge, his lawyer. He has a challenging role, but he makes the transitions between parts feel effortless.

This is a beautifully crafted character study which puts the spotlight on one of science's greatest contributors and makes us think about the connection between science and religion. Galileo managed to reconcile the two - can we? It's an admittedly personal question, but the point is, this is not just a history lesson, it's a thought-provoking and captivating piece of theatre.

Remotegoat, Edwin Reis

![]()

Icarus Theatre fly into London on waxen wings, which, after this compelling production, show no sign of melting any time soon. ‘The Trials Of Galileo’ delivers a rich flow of insight and information into the mind of a man hailed as one of the fathers of modern science. From his home in Florence with his cherished telescope, to conversing with the Pope in the Vatican Gardens, we follow Galileo Galilei on his laboured journey to clear his name of heresy following the publication of his book, which had the audacity to sympathise with the Copernicus Theory – that the Earth orbits around the Sun, rather than vice versa.

Sustaining an audience’s attention in a one man show is no mean feat for an actor, but to say that Tim Hardy has been around the block is an understatement; his impressive CV includes spells with the RSC, on the West End, where he worked extensively with Peter Brook, and even international tours as an Opera singer. Hardy has previously worked with writer/director Nic Young on an episode of the BBC’s ‘Days That Shook The World’ called ‘Galileo’, and it was from here that the idea of this stage production was born. A collaborative project between the two ever since, the feeling of utter ownership and comfort that Hardy brings to the role is refreshing to behold. With seemingly minimal effort, he holds us in the palm of his hand for the duration, expertly manoeuvring through the peaks and troughs of hope and despair poor Galileo is subjected to, despite the unfortunate distractions of rather loud traffic – oh the perils of a pub theatre!

The writing, too, is faultless, and it would be easy to mistake the text for an early forgotten masterpiece by Stoppard or Bennett. There are some cracking lines, such as when Galileo describes the infamous Rack as a “verbal laxative”. Period-sounding enough to fit the world, yet contemporary enough to be easily digested, Young finds plenty of opportunity to lighten the tone, often peppering the dialogue with modern expletives, which for the most part feel perfectly natural.

The issue with a 70 minute monologue is, so often, how to create a feeling of time passing, and indeed location, without painfully obvious verbal exposition. The production suffers slightly here, with Galileo teleporting across Italy without much in the way of explanation. Jumping from retrospective analysis to in-the-moment-action, it is never quite clear where or when Galileo is supposed to be when he is addressing us directly.

This is a fine production, and a fantastic example of a writer and performer at the top of their game. The one query would be – why this story? Why now? Whilst intriguing, informative and entertaining, it is a struggle to relate much of the content to any contemporary issues. This is indeed an enthralling story, but on one level feels less like a play, and more like the best history lesson ever.

The Public Reviews, Ray Taylor

![]()

Tim Hardy stars in this one-man tour de force as Galileo, put on trial in 1633 for heresy. Whilst the play focuses on the events of that trial, it also skilfully relates other incidents in Galileo’s life up to and beyond the trial. In 1632 Galileo asserted his belief that the Earth revolved around the sun, rather than being the centre of the universe and wrote a book about it. The Catholic Church banned it and the Inquisition forced Galileo to denounce his own work as heretical. He was subsequently placed under house arrest but during his confinement he wrote another work which would inspire others such as Isaac Newton to further challenge Biblical doctrine.

Tim Hardy certainly looks the part in a visually authentic costume and grey beard (his own). The performance lasts for 75 minutes without a break and Hardy inhabits the stage with assurance, sometimes addressing the audience directly, while at other times lost in his own ruminations. He demonstrates a full gamut of emotions including anger, bitterness, frustration, despair, fear, satire, humour, enthusiasm, surprise. His scene “with” the Pope is so expertly done it is as if there was, indeed, another actor on the stage. The only lapse in an otherwise acclaimed performance is an occasional drop in his voice with some inaudible speech.

The props and furniture are few but atmospheric: a main desk with a red cloth, a smaller table with pitcher and glass of water, a stool, the iconic telescope, papers strewn about on the desk and floor, a book – but all of these are skilfully used and woven naturally into the production. There is also very occasional use of music that is good and is, if anything, underused.

Galileo is portrayed as something of an innocent in a world of political machination. His somewhat naïve belief in the evidence and his scientific reasoning did not save him from a papal reprimand and from having the full weight of the Catholic church thrown against him. He certainly understood the science better than anyone else, but could never quite grasp the politics.

If you know nothing at all about Galileo before seeing this play you will come away enlightened and entertained and it is predicted that you will seek further knowledge about him at the earliest opportunity.

Reviewed on: 5 February 2015

Three Weeks

![]()

Galileo Galilei, wonderfully outlined by Tim Hardy in this one‐man show, lets the audience look into his heart when he takes them on a most personal discourse of his famous trials. Deeply Catholic, Galileo has indubitable proof that the Sun is the central point of our universe; Catholic dogma, on the other hand, states that Earth is the centre of God's creation. So how do you live with knowledge? Do you choose truth or life? With a delicious dollop of sarcasm and wit, Hardy attempts to describe such inner conflict. A fine and sarcastic play full of thought‐provoking contradiction, it is as soul‐breakingly bitter as it is heartbreakingly humorous.

British Theatre Guide, Graeme Strachen

![]()

Sitting quietly within his chamber, an ageing Galileo Galilei ponders the cards that fate has dealt him, recounting the sham and mockery that was his trial and the events which lead him to write the book which almost led to his death. Tim Hardy's portrayal of the legendary astronomer is an excellent piece of theatre. As we are gently led through the years by his kindly yet incisive wit, Hardy keeps a thinly veiled intelligence ever brooding beneath the surface of the man. His descriptions of the trial itself create a palpable feeling of being in the presence of the era, and it becomes almost impossible to remember that the audience is watching an actor and not the real man somehow magicked upon the stage. With great levels of detail, it's a joy to listen to the stories which surround this fascinating period of Papal dominance and fear. The only slight quibble with the production is the unfortunately weak ending, which was necessitated by the lack of detail after the trial. Otherwise a solid piece of theatre that won't disappoint audiences this Fringe.

Fringe Review, Chris Hislop

![]()

The life of Galileo Galilei is an often‐plundered tale, and for good reason: not only did his discoveries take us a huge step further into understanding the cosmos, but his struggle for reason against the church is an ideal metaphor for any struggle against oppression, especially of a religious nature. In this retelling, written by Nic Young and performed by Tim Hardy, Galileo's struggle is shown from all possible angles and analysed legally, scientifically and politically, as well as personally. The powerful performance, along with the pacey script, make for a great evening's entertainment… This particular production focuses on Galileo's trial: the moment when the Catholic Church condemned a book he had written, a philosophical discussion of the Copernican universe (Earth revolving around sun), and the mis‐trial that led to his house arrest. The trial is examined in meticulous detail: and although we jump around in time a little, the focus is on the discussions before, during and after the trial: the dichotomy between two views of the universe, mostly.

This cerebral discussion is made human and entertaining by giving Galileo a passionate case to argue, and it is a credit to Tim Hardy that he could take something so discursive and turn it into engaging drama. The occasional scene involved him jumping between characters, but the play was most alive when he was just Galileo, just the poor man in his house, replaying his actions in his mind. A tour‐de‐force from this fine actor! …It is a fantastic show, well worth seeing and a delight for anyone interested in theatre: if I could give 4 and a half stars I would!

Fringefan.info, Sean Davis

![]()

Galileo describes his Inquisition trial for violating an edict that proscribed advocating Copernicus' theory that the Earth revolved around the sun. During his thorough discourse he covers the effects of the rack, his own astronomical studies, his friendly meetings with Pope Urban, and the legal maneuvering during the trial. All the pieces fit nicely together to explain the verdict and his ingenious recanting.

AOUP, Brian Lavercombe

The Trials of Galileo

at

t

he Burton

-

Taylor Studio Theatre

-

various

dates in January

2016

My own experience of one

-

person drama is very lim

ited

-

a

powerful performance

many years ago by Steven Berkoff in Los Angeles, Simon Callow brilliant as

Charles Dickens and those marvellous short TV plays by Alan Bennett

-

so I wasn't

very sure what to expect in going with AOUP colleagues to see Nic Young's solo

drama,

The Trials of Galileo, performed by RSC actor, Tim Hardy.

The theatre, part of the Oxford Playhouse establishment, has an extremely

constricted site, with no foyer, but a small porch leading through narrow passages

and stairs to the tiny

auditorium. This is hardly the stage to show

'all the world', but

is perhaps an appropriate place for the concentrated focus of one

-

person drama. It

certainly worked in this case.

The play presents the famous Italian scientist and mathematician, Galileo Galilei,

recounting and commenting on his terrible and humiliating experience of trial by the

Inquisition in Rome during the Spring of 1633. He was accused of heresy in

promoting the heliocentric theory of the heavens

-

that the earth and other planets

revolve around the sun. This was in contradiction to the assumption, long held by

the Church,

that everything clearly revolved around the earth, which must be

stationary as the centre of God's creation. Galileo was not the originator of

heliocentrism. Nearly 100 years earlier Copernicus had shown that it was possible

to predict the motion of the heavenly bodies much more easily and accurately with

a sun-centred system. What Galileo did however, as one of the first great

experimental scientists and using his own

greatly improved telescope, was to

provide observational proof that compelled open-minded scholars to accept the

truth of the heliocentric theory. Galileo was a devout Catholic. He was supported by

the Medici ruler of Tuscany and had had friendly debates

on natural philosophy with

21

the Pope himself

-

he thought he was safe in publishing his work. What Galileo

couldn't understand however, was that for the Papacy this was not a matter of

scientific proof or truth, but a vital matter of religious politics and

power

-

the

Church could never be proved wrong on a major fact of dogma. This was perhaps

the first great confrontation of science and religion. It would not be the last.

Tim Hardy gave us a brilliantly persuasive performance. By turns confident, witty,

uncertain, puzzled and angry, he presented a Galileo totally believable as

someone proud of his work

yet desperate to prove that this cannot be contrary to

God's wishes. With no scene changes and few props

-

a table scattered with his

papers and charts, and the vital telescope standing in a corner

-

he was able to

create the differing atmospheres of Galileo's own study, the courtroom and Vatican

gardens and project the characters of the court prosecutor and Pope Urban VIII in

their verbal tussles with Galileo. Particularly moving was Hardy's portrayal of

Galileo's human frailty in yielding to the court's threats of torture and death and

recanting on the value of his own work

-

a denial which so nearly broke his spirit.

Nearly but not quite

-

as he was led from the courtroom, Galileo is supposed to

have muttered,

Eppur si muove,

'and yet it moves'.

I found this an inspiring piece of theatre. Thank you AOUP, for spotting it and

giving us the chance to enjoy it.

Southside Advertiser, Tom King

Galileo Galilei is a name probably more familiar to many people now due to a line in Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" or the name of a NASA probe investigating the planet Jupiter, but who was he?

Well, Galileo Galilei was an Italian genius of his day (1564 to 1642) - a mathematician, astronomer, physicist, philosopher and general inquiring mind of how everything worked, and it is that inquiring mind that questioned everything around him that ultimately brought him into almost fatal conflict with the authority, church, and state (they were pretty much all one) of the day.

General astronomy was always a childhood fascination of mine, and Galileo with his observations that, contrary to the teachings of Aristotle and the Bible, the Earth and the known planets did in fact move and revolve around the sun brought him to my interest too as a child. Galileo was also a scientific instrument maker and made custom telescopes for clients too. One of his own hand built telescopes was the best of its time and its unique 32x magnification had allowed him to witness things in the sky that no man had ever seen before...things like the terrain of the moon, the shifting phases of Venus, sun spots, and the moving four moons (all they could see at the time) of Jupiter. I was then curious to see how this subject would work as a solo performance on stage.

For this review, I am going to leave the science and ideologies of the day alone as although this work is about them, they are almost at times side issues to the politics of the day that were the real issue here, and Tim Hardy as Galileo does an excellent job of enlightening the audience into the basics of the science and Church doctrine as this one hour play develops anyhow (and learning some of that is part of the pleasure of this work).

Tim Hardy does a very skilful job of immediately pulling his audience into the story. We start with a man just after the sentence of the court. Galileo is 70 years of age, has been on trial for three months and to avoid torture (and probably death) has been forced to sign paperwork disclaiming his theories. As well as that, he is under house arrest for the rest of his life, he may neither publish, discuss or teach any more of his theories of planetary motion, and his book on it is banned.in short his career as a questioning scientist and mathematician is over, his reputation is in ruins.

From this starting point, Tim gives us a man questioning his weakness in not standing up for his ideals, his stupidity in believing that his work was with the blessing of "The Pope himself", and his belief that he could somehow in his work discuss (even as philosophical debate) the earlier banned work of astronomer Copernicus.

Galileo may have been a genius, but he was also a bit of a na´ve fool in not understanding the politics of Church and State of his day, and this performance brings that over gently, but forcibly. This was a man who simply had to be silenced at any cost. The authorities of the day controlled everything by the word of the Bible. Anything that questioned that, questioned them...simple as that.

The trial of Galileo was a farce of a mock trial. The guilty verdict was already written the moment the letter advising him to go to Rome was written.

I liked this show a lot. It does what only live theatre can do, and that is allow a master story teller like Tim Hardy to draw an audience into their story and world. That need to be captivated by a story teller is probably one of the oldest responses in man, and theatre does it in a way that just does not work on the same level in other media such as film or television.

This is a moving performance depicting a man who at the height of his fame was crushed by the full weight of the Church State. Somehow though, Galileo may have lost his faith in the people of the church, but he never lost his faith in his religion and his God, and that is powerfully shown at the very end of this performance.

This is a thought provoking piece of work by an obviously talented creative team that includes amongst others Nic Young (writer & director) and Max Lewendel (producer).

The Times of Malta, Paul Xuereb

Furiously beautiful minds

The Trials of Galileo

Palace Courtyard, Valletta

In the same manner that challenging authority in the light of scientific reality was the only logical step forward for some of the greatest thinkers of the renaissance and the enlightenment, the International Science Theatre Festival was a great way of confirming that the arts and sciences have room to stand not only side by side but also to work collaboratively.

The first play on offer was a British one-man play: Icarus Theatre's The Trials of Galileo, written and directed by Nic Young and interpreted by Tim Hardy. This hour-long address to the audience explained Galileo Galilei's plight and his subsequent loss of the fight against the Catholic Church in his trial at the Vatican, for having documented and written an argument which proved that previously held beliefs about planetary movements were wrong and that it was in fact the sun which was the fixed point around which all the other planets moved.

In other words, he'd proved that the world was not the most important planet in the cosmos for having everything else revolve around it: God's greatest creation had a greater fixed point controlling it which it simply had to look up to. The entire piece explores not only Galileo's conflict with the Church and the indignity of being forced to refute his own work, but also the internal conflict which this man - a good Catholic but an enthusiastic scientist and voracious explorer of the skies - had to grapple with.

The beauty of the piece lay in Hardy's excellent interpretation of the different people he had to deal with during his trial and the events which led up to it - from the judge to the Pope himself. His vocal modulation and subtle tonal changes made his story engaging and compelling to a contemporary audience while reminding them that greatness comes at a price and, more often than not, the benefits of one's endeavours are not enjoyed or even recognised till years later.

The man with the most accurate telescope, whose vision changed our perception of the world, was human and vulnerable to forces greater than he could handle - though he gave them a good run for their money.

In terms of theatrical value, Hardy's strength lay in his crisp characterisation and his nuanced vocal control, making it a highly engaging piece.

Martin Prest

Some VERY EXCITING news. Tomorrow night I will be in the audience for The Trials of Galileo, a thrilling one-man show starring Tim Hardy.

I saw this show four years ago at the Edinburgh Fringe and it was spectacular. It inspired me to adapt and perform A Christmas Carol, a show I have toured for four Christmases now. My first foray into the beguiling world of one-man performance… Galileo imbued me with a love of the one-man stage show and the craft of it. I find the concept – and performing them – fascinating.

The Stage, Gerald Berkowitz

Because the Renaissance Catholic Church claimed infallibility and absolute authority, and because the Bible seemed to describe an earth‐centred universe, any scientific assertion to the contrary was a threat.

Called before the Inquisition to recant his assertion that the earth revolved around the sun, Galileo was at first confident and disdainful because, as he explains in this monologue by Nic Young, he had carefully structured his writings to stay just within canonical edicts and had the personal assurance of Pope Urban that this ploy would be acceptable. But popes can change their minds, religious and secular politics can require sacrifices and scapegoats, and the mere fact that you happen to be right and can prove it is not as significant as who your friends and enemies are.

Tim Hardy plays Galileo, capturing the intellectual rigour and deep faith of the man, along with an attractive sense of irony, an admittedly dangerous degree of unworldliness, and a haunting sense of guilt that pure fear of torture led him to recant. Script and performer carry us clearly and gracefully through a lot of history and science, so that we always understand both the issues and the politics, while painting a multifaceted and always sympathetic portrait of a complex man in an even more complicated situation.

The Scotsman, Susan Mansfield

Galileo's conflict with the Catholic Church is often seen as a clash between religion and science, entrenched belief getting in the way of scientific progress. This one‐man play, written by Nic Young for the 400th anniversary of Galileo's discoveries, reveals the situation to be more complex.

Exploring in detail Galileo's trial for heresy, at which he was required to renounce his belief that the Earth moves around the Sun, Young suggests that Galileo's real weakness was his failure to understand the politics unfolding around him.

A genius at astronomy, he was less adept at discerning the machinations of his fellow men; when Pope Urban VIII seemed to give support to his book, Galileo made the mistake of believing him.

Actor Tim Hardy creates a suitably complex portrait of the scientist, now in advancing years: naive, impulsive, excitable, yet feisty, occasionally sardonic. He is angry at being held under house arrest even though he has recanted, but at the same time wonders if he should have stood by his beliefs and been martyred. One can't leave this play and not be wiser about the man, his predicament and its lasting implications.

Camden New Journal, Jack O'Connor

Was the Italian mathematician and astrologist Galileo Galilei the first whistleblower? After all, he alone took on the Pope by proving that the Sun was the centre of the universe and not the Earth, contrary to doctrinal teaching.

Nic Young’s one-act play reminded this hack of the old adage that “reporters are like whores and bartenders but spiritually like Galileo” because they know that the world is round, unfortunately their editors know that the world is flat.

Young premiered this production in the US in 2009. Tim Hardy returns as Galileo, giving a very spirited and engaging performance of the great man, holding the audience throughout the evening. Sadly, with the rise of religious fundamentalism one can see the relevance of the drama, which is certainly not lacking in humour or irony.

Bertolt Brecht wrote The Life of Galileo with music by Hanns Eisler, both German exiles in the US having escaped Nazi Germany. There are allusions to Marxism in the Brecht piece; however, Nic Young wisely keeps contemporary politics out of his Trials.

Costa Blanca News

Rewarded twice over

The Javea Players haven’t done it overnight. They were after all established in 1976. They did for far too long wander like theatrical gypsies from venue to venue to stage for the ex-pat community a little of the theatre they had bartered for a bit of sunshine and an affordable gin and tonic. But, boy they've done it now. In the little street behinds the now defunct Bookworld, they have built the first real theatre in Javea. What’s more, they have attracted into their bosom sound engineers, lighting technicians and set designers who can do deliver the highest professional standards. And, they have developed an ethos that the most important component of any theatrical production is the audience and an absolute that their appreciation of the theatre should never be underestimated. Such conviction has been well rewarded with capacity audiences for theatre in the round and thought provoking productions such as “Duet for One.” What a real treat, thought the Javea Players’ management, it would be for such audiences if they could find the way to bring to their Studio Theatre a professional production from the UK. They did just that last week. (March 24 to 28) Not just any professional Production but one that had won for its author, Nic Young and its performer, Tim hardy the highest acclaim in America and the UK.

The production on the Javea Players’ stage was described by one Costa Blanca critic as “One Amazing experience.” Now, I don’t know if you would find it slightly selfish but although Javea Player’s Chairman, Tony Cabban takes great pride in the society rewarding the loyalty of their audiences, he likes, from time to time, to the members a little extra reward. This time the reward wasn’t going to be that small. Tim Hardy is a director of the RADA summer course, a director of the ten-week drama course at the New York University and is a member of RADA’s admission panel. Tony Persuaded Tim to run a theatrical workshop for Javea Players’ members last Saturday (March 29.) Then, the reward for the Players members was doubled. Tim’s wife, the acclaimed actress and associated teacher at RADA, Allison Skillbeck who had come over to join Tim for a short holiday, agreed to join Tim in staging a RADA workshop for Javea Players’ members. I’m told that those attending this workshop did not only feel it had been a privilege to have played a part in the presentation of such phenomenal theatre as “The Trials of Galileo” but also to have had the benefit of such expert tuition and the company of actors with such endearing devotion to the theatre to be a marvelous experience.

Costa News

One man, one play, one amazing experience.

The Javea Players policy of offering a wide range of theatre experiences surpassed all previous highs when they booked guest actor Tim Hardy to present his one man show, The Trials of Galileo, at their Javea Studio Theatre on Monday March 24. RADA trained Tim held the audience spellbound from beginning to end with his passionate, funny and thought provoking highlights outlining the dramatic events surrounding Galileo's heresy trial in 1633.

Through the invention of his new telescope, he declared that he had indubitable scientific proof that the sun is the central point of our universe. Catholic dogma, on the other hand, stated the Earth is the centre of God's creation and in 1616 the Inquisition basically issued a gagging orderrefraining him from holding, teaching or defending his theory any further.

The astronomer was dumbfounded, he knew his findings were correct and failed to reason why the church would not open its mind on discussion. Unfortunately he didn't understand until it was too late that church rules were not about reason, logic, and scientific fact, they were about religious politics.

He was eventually tried for heresy, forced to admit his 'sins' to avoid the death penalty, found guilty and sentenced to house arrest for life.

It was from this prison Hardy portrays Galileo's inner conflict, displaying a bewildering range of emotions that had everyone sitting on the edge of their seats, totally mesmerised by the light and shade talents of delivery of this superb charismatic actor, that at times reflected the rapid and urgent exciting rhythm of the rap genre.

To quote a line from the story, during the thought provoking silent moments, "You could have heard a mouse fart".

Tim works with the Royal Shakespeare Company and has directed and performed in many productions across the UK, Europe, and the United States.

As well as numerous musicals, operas and films, he has also performed in television programmes for the BBC and ITV including Casualy, The Bill, Eastenders and The Sweeny.

Round Town News, Jack Toughton

Galileo is simply 'magnifico' by Jack Toughton,

THEATRE ON the Costa Blanca went into orbit with the visit of verteran actor Tim Hardy as he held an audience spellbound with his hit one man show The Trials of Galileo.

THE SCIENTIST took on the Italian establishment and lost by proving the planets moves round the sun, falling out with the Roman Catholic Church and its doggedly held view- for the common man at least- that the earth was the centre of the universe. As a result Galileo was found guilty of heresy in 1616 and under house arrest following a fixed trial at the behest of the Pope. He sensibly signed a confession recanting his findings and escaped torture on the rack, also avoiding the fate of a Franciscan monk who earlier promoted the same view and was burnt at the stake. Written and directed by Nic Young, Javea Players must be congratulated for this new venture, importing professional theatre for a show at the group's studio theatre.

MAGIC

And so for around 75 minutes Mr. Hardy, who trained at RADA and has performed with the Royal Shakespeare Company, stood centre stage and performed theatrical magic. He has directed and performed across the world and taken roles in numerous musicals, operas, and films, as well as on UK television, where he is also in demand as a successful narrator- thus the silken tones. The success of the show is its language- these might be complicated historical matters but the script wonderfully and faultlessly brought alive by the actor are very modern- and it helps get the grey matter going. As a scientist who has the mathematics to prove a crucial theory, we meet a Galileo who despite the anguish of a rigged trial and fears of an uncertain future, reflects on his lot. Hardy brings out all the emotions of the piece. We are treated to plenty of humour. His Galileo remains proud of his achievements, scornful of the establishment, and deeply religious- but when making peace with God as the creator, concludes that the earth and planets are still orbiting the sun.

IBJ.com (Indianapolis Business Journal)

A full house greeted Butler University visiting artist Tim Hardy for the first of a two‐show‐only stint in Nick Young’s one‐man play “Galileo” (Sept. 9‐10)… The quality of the performance I found inspiring. Seeing this level of excellent work can be intimidating, but I hope that it also proves inspiring.

Hardy – a faculty member of the Royal Academy of the Dramatic Art who appeared in such landmark productions as Peter Brook’s “Marat/Sade” and Peter Hall’s “Henry V” – created a weary, funny, sad Galileo angry at himself for misjudging the forces against him. His explanation of the power of the rack as a torture device effectively painted a flesh‐and‐blood picture of the consequences of his alleged heresy. It brought humanity to his brilliance, taking this from history lesson to an evening of theatre.

Dawn Smallwood Blogspot

Curiosity and intrigue leads one to see this one man production, produced by Icarus Theatre, at Halifax's Square Chapel at the end of January.

Galileo's trial to heresy in 1533 is narrated by Tim Hardy in a small compact space with neatly arranged laid out props which sets its context. The trials and tribulations of Galileo were linked to the books he wrote about new astronomical discoveries following construction of his telescope in 1610. He is an extraordinary individual with a passion for science including physics, mathematics, philosophy and significantly astronomy.

His discoveries of the solar system particularly its relationship with the earth caused controversy among astronomers and eventually to the religious leaders at the time. The church felt that the discoveries and proof were a threat to one's faith and this led to his trial.

Galileo has been known as the 'father of modern science' and his telescopic contributions no doubt led to the development of astronomy. This created a nucleus for key discoveries particularly with Isaac Newton, the Enlightenment era and also Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking in the 20th Century. The findings and its proof has influenced many to see the earth in a different perspective.

Seeing The Trails of Galileo has opened up ones curiosity to continue discovering whether its science or the arts. This production is projected with simple but effective lighting and soundscapes which set the characters mood with a wide range of emotions expressed throughout. It's currently touring in England and Ireland at the moment. Please click on the schedule.

Norman Bissell - Edfringe.com

The superb Tim Hardy triumphs as Galileo in this top notch production by Icarus Theatre. His acting is outstanding in a spellbinding story of the conflict between scientific truth and political and religious power that remains highly relevant in today's world. A 5 stars must see for Fringe goers, can't recommend it highly enough. As a Fringe accredited promoter, I'd love to be able to bring it to the Atlantic Islands Centre on the Isle of Luing through The Touring Network.

|

Newsletter

Enter your details to receive free ticket offers and info on upcoming shows.

The Trials of Galileo by Nic Young

Fringe Review

Wandsworth

Edfringe.com

Three Weeks

Remotegoat

Public Reviews

Fringe Guru

Broadway Baby

ViewfromtheGods

British Theatre Guide

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

or better

in 15 of 17 reviews

Out of all productions with a star rating in the last 3 years:

or better

in 36 of 45 reviews

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"Max Lewendel's production succeeds by the strength of its acting and the steadily increasing tension."

Jeremy Kingston, The Times

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"Directed so specifically that the beast of chaos that charges through Ionesco's work like his own rhinoceros is safely routed through the play."

Rebecca Banks, Ham & High

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"A daring production by an energetic new company, the London-based Icarus Theatre Collective, it pulls no punches in its visceral pursuit of pure absurdism."

Daniel Lombard,

South Wales Argus

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

Premiul special al juriului

Special Jury Prize:

Cash prize from Romania

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

Premiul pentru cea mai buna actrita ín rol principal

Best Actress in a Leading

Role: Amy Loughton

Coyote Ugly by Lynn Siefert

"Scarlet, a wild 12-year-old, like a coyote bitch on heat".

John Thaxter, What's On

Journey's End

by R.C. Sherriff

The Times

The Scotsman

Manchester Eve News

Macbeth

by William Shakespeare

With sword, axe, spear and bare fist fighting it is an impressively energetic and dynamic production.

Victoria Claringbold, Remotegoat

The Trials of Galileo

by Nic Young

Icarus Theatre fly into London on waxen wings, which, after this compelling production, show no sign of melting any time soon.

Edwin Reis, Remotegoat

Spring Awakening

by Frank Wedekind

Nigh-on Faultless. The cast are, one and all, magnificent.

Roderic Dunnett, Behind the Arras

Macbeth

by William Shakespeare

"Max Lewendel's production is fast-paced and pulls the audience straight in... Outstanding".

Von Magdalena Marek, Newsline

Macbeth

by William Shakespeare

"Particularly haunting is the piece because of the use of music and sounds, designed by Theo Holloway. The effect is outstanding".

Von Magdalena Marek, Newsline

Macbeth

by William Shakespeare

"Max Lewendel's production is fast-paced and pulls the audience straight in... Outstanding".

Von Magdalena Marek, Newsline

Macbeth

by William Shakespeare

"The play explodes into action with a high-powered fight sequence using real swords, axes and spears that superbly captured the intensity of battle".

Robin Strapp, British Theatre Guide

Coyote Ugly by Lynn Siefert

"The five-member cast fill the dim confines of the theatre like a desert storm".

Le Roux Schoeman,

Church of England Newsletter

Coyote Ugly by Lynn Siefert

"This sexy, steamy drama really hits home, especially after delivering the scorpion sting in its tail".

Philip Fisher,

British Theatre Guide

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"Comedy, tragedy, fear, mystery, sex, violence, disturbance: The Lesson has them all".

Eleanor Weber,

Raddest Right Now

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"It is impossible not to enjoy Icarus Theatre Collective’s production of Ionesco’s one-act play".

The Stage

Coyote Ugly by Lynn Siefert

"The cast navigates the perilous emotional terrain with aplomb".

Visit London (Totally London)

Coyote Ugly by Lynn Siefert

"Sizzling bursts of desire and hate among the North American sands".

Timothy Ramsden,

Reviews Gate

Albert's Boy

by James Graham

"Extraordinary...

Victor Spinetti is outstanding."

Cheryl Freedman,

What's On in London

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"The Icarus Theatre collective's production of Eugène Ionesco's absurdist masterpiece is brilliant. A fast-paced, sixty-five minute screaming journey from a bare classroom into utter chaos."

Kevin Hurst, Extra! Extra!

Many Roads to Paradise

by Stewart Permutt

"You would pay a lot of money in the West End for a class act like this, so why not pop along to the Finborough and find out what great nights are made of."

Gene David Kirk,

UK Theatre Web

The Time of Your Life

William Saroyan

"Book as soon as possible!"

-Claire Ingrams,

Rogues & Vagabonds

The Time of Your Life

William Saroyan

"This is the kind of consoling play we need right now."

-Jane Edwardes, Time Out

Romeo & Juliet

William Shakespeare

"A rollercoaster rendering of the play that dragged the audience on a fast-paced soul-stirring ride for two heart-rending hours."

Romeo & Juliet

William Shakespeare

"An excellent take on a globally-renowned tale of true love."

Romeo & Juliet

William Shakespeare

"Props to Icarus Theatre Collective for putting on such a fantastic show."

Romeo & Juliet

William Shakespeare

"A fresh and invigorating version of this time-honoured romantic tragedy."

Darlington & Stockton Times - Christina McIntyre

The Time of Your Life

William Saroyan

"Fine performances from the 26-strong cast."

-Michael Billington, The Guardian

The Lesson Eugène Ionesco

"You can reach out and touch the emotional atmosphere."

-Julienne Banister,

Rogues & Vagabonds

About Us

About Us

-

-